In exactly one week, my novel SNAKESKINS will be published. That’s a good thing! And yet I’m feeling… I don’t know. Mixed. Mixed is how I’m feeling.

Here’s the thing. I’ve really enjoyed the long lead-up to publication of this novel. I sold it to Titan Books (…checks calendar…) eleven months ago. I wrote a bunch of additional material in September, signed off on the copyedit in October, received final proofs in January. Since that point the book has been complete, simply waiting to become a real object. I held an ARC copy in my hands in February, then a copy of the real actual book earlier in mid-April.

But even now, with hundreds of actual, tangible copies of the novel having been printed in two continents, the book remains unreal. In one week, on 7th May, the novel will be available to purchase in the UK and the USA. And I’m not ready for it.

This whole long period has been characterised by positivity. SNAKESKINS secured me a two-book deal and an agent. The ARCs were sent to authors I admire a huge amount, who not only read the book, they provided the most incredible blurbs. At various events, friends and friends-of-friends have wholeheartedly wished SNAKESKINS all the success in the world. The goodwill I’ve been receiving has been overwhelming.

I’m not saying that this goodwill is an illusion, or that it’ll evaporate in a week’s time. But I appreciate that all this goodwill is just that – a pleasant wish. In many ways, I’d prefer to stay in this period of daydreams and potential rather than face the hard reality of reviews and sales figures.

I can’t help myself from trying to read the tea leaves about how this is all going to pan out. There’s not a huge amount to go on, and I’m only slightly ashamed to confess that recently I’ve been googling the phrase ‘Tim Major Snakeskins review’ at the beginning and end of every day. But each of these tea leaves* gives me a Good Feeling:

Tea leaf 1: Titan Books are in a fantastic place right now. Within just the last couple of months they’ve published M.T. Hill’s deliriously inventive ZERO BOMB and Helen Marshall’s THE MIGRATION, which is as close to perfect as you could reasonably expect. I’m just about to dive into David Quantick’s ALL MY COLORS, which from the blurb sounds so much my thing that I’m cross that I haven’t written it myself. James Brogden’s THE PLAGUE STONES is out in a couple of weeks and Aliya Whiteley’s SKEIN ISLAND will follow soon. I can’t tell you how happy I am to be in the company of such writers.

Tea leaf 2: The guys at Titan, and my agent, are friendly and not really scary at all. Seriously, they’re lovely. Considering they’re THE GATEKEEPERS to this industry, they’re doing kind of a crappy job of being fierce and forbidding. I had lunch with Cat and George from Titan a couple of weeks ago and we talked about books and films and Art Garfunkel and it was as if they were just interesting normal people, which obviously is madness.

Tea leaf 3: The Titan marketing team are clearly incredible at their jobs. There’s going to be a book blog tour, beginning the day before publication! And over the last few days SNAKESKINS has been popping up in the feeds of Instagram book bloggers. Each sighting of Julia Lloyd’s incredible cover gives my heart a little sharp prod.

Tea leaf 3: The Titan marketing team are clearly incredible at their jobs. There’s going to be a book blog tour, beginning the day before publication! And over the last few days SNAKESKINS has been popping up in the feeds of Instagram book bloggers. Each sighting of Julia Lloyd’s incredible cover gives my heart a little sharp prod.

Tea leaf 4: THAT COVER. When I visited the Titan office I met Julia Lloyd, the seriously talented cover designer, and I swear I thanked her seven times. It was only back when I was shown the cover that I first allowed myself to believe that a bookshop customer might actually pick up my book and buy it, and they totally should because even the spine is awesome and it’ll look really good on their shelf. Also: a great use of spot varnish.

Tea leaf 4: THAT COVER. When I visited the Titan office I met Julia Lloyd, the seriously talented cover designer, and I swear I thanked her seven times. It was only back when I was shown the cover that I first allowed myself to believe that a bookshop customer might actually pick up my book and buy it, and they totally should because even the spine is awesome and it’ll look really good on their shelf. Also: a great use of spot varnish.

Tea leaf 5: THOSE BLURBS. I’ve bumped into a couple of the authors since they provided blurbs, and I looked deep into their eyes, Larry David-style, and still they swore that they liked the novel.

Tea leaf 6: There have been a couple of early reviews, and they’re good! Booklist called it a ‘taut and fast-paced sf thriller’ and Publishers Weekly used phrases like ‘delightfully tense’ and ‘uncanny tale’ and ‘strong voice’. There are currently three Goodreads reviews (book bloggers, I presume), with one of them giving it 5 stars. I’m prepared for the bad reviews, really I am, and in the past I’ve rarely disagreed with criticisms and not felt too badly stung. But good reviews are good.

Anyway. This time next week the book will be out in the world, and either it’ll be liked or it won’t, and either it’ll sell well or it won’t. I’ve already delivered my second novel to Titan (it’s unconnected to SNAKESKINS), I’ve more or less completed a novella and I’m planning a bigger, weirder novel. My only ambition thus far has been to be allowed to keep writing, and to spend more time writing, by making it a legitimate part of a cobbled-together career. I’m writing more than I ever have before, so I’m winning on that score.

It’s only right to acknowledge that I do have a fair amount at stake. SNAKESKINS isn’t my first novel but I feel wholehearted about it. If it crashes and burns, it’ll hurt.

So all of this is why I’m trying to pay full attention to this moment, when there’s only potential, when I feel able to introduce myself to people as a writer and feel halfway convinced that that might actually be my valid identity, when I’m swimming in goodwill, when at times I’m able to imagine that this whole thing might actually turn out well.

It seemed important to write this blog post to capture a snapshot of a particular moment. I promise to provide an update from the other side. Wish me luck?

* Clearly, I have no idea how tea leaves are supposed to be read.

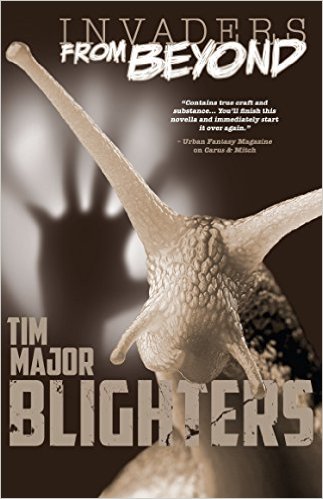

BLIGHTERS is out today! It’s available as an ebook from

BLIGHTERS is out today! It’s available as an ebook from

You must be logged in to post a comment.